The planet Jupiter is particularly known for the so-called Great Red Spot, a swirling vortex in the gas giant’s atmosphere that has existed since at least 1831. But how it formed and how old it is remain matters of debate. Astronomers in the 1600s, including Giovanni Cassini, also reported a similar spot in their observations of Jupiter that they called the “Permanent Spot.” This led scientists to wonder if the spot Cassini observed is the same one we see today. Now we have an answer to that question: the spots are not the same, according to a new paper published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

“From measurements of size and motion, we concluded that it is highly unlikely that the current Great Red Spot was the ‘Permanent Spot’ observed by Cassini,” said co-author Agustín Sánchez-Lavega of the University of the Basque Country in Bilbao. , Spain. The “Permanent Spot” probably disappeared sometime between the mid-18th and 19th centuries, in which case we can now say that the lifespan of the Red Spot exceeds 190 years.”

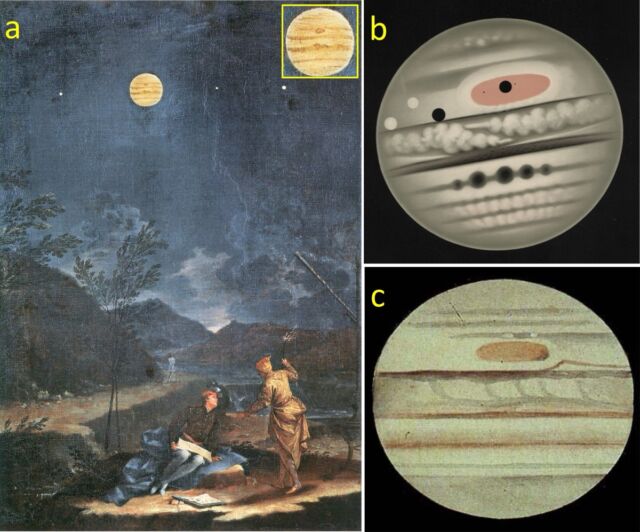

The planet Jupiter was known to Babylonian astronomers in the 7th and 8th centuries BC, as well as to ancient Chinese astronomers; The latter’s observations would eventually give birth to the Chinese zodiac in the 4th century BC, with its 12-year cycle based on the gas giant’s orbit around the Sun. In 1610, aided by the advent of telescopes, Galileo Galilei famously observed the four largest moons of Jupiter, thus strengthening Copernicus’ heliocentric model of the solar system.

Public domain

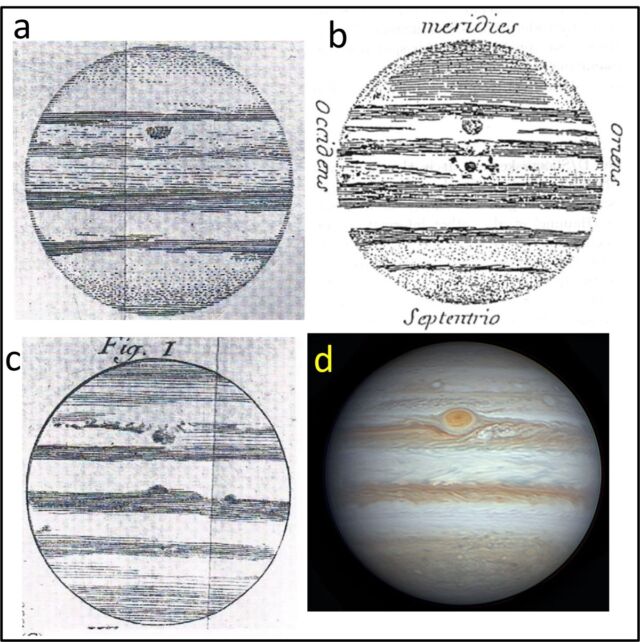

It is possible that Robert Hooke may have observed the “Permanent Point” as early as 1664, with Cassini following suit a year later and a few more sightings during 1708. It then disappeared from the astronomical record. A pharmacist named Heinrich Schwabe made the earliest known drawing of the Red Spot in 1831, and by 1878 it was again quite prominent in observations of Jupiter, fading again in 1883 and the early 20th century. to.

Maybe the country is not the same…

But was this the same permanent spot that Cassini had observed? Sánchez-Lavega and his co-authors set out to answer this question, combing through historical sources – including Cassini’s notes and drawings from the 17th century – and more recent astronomical observations and evaluating the results. They performed a year-by-year measurement of the sizes, ellipticity, surface area and motions of the Permanent Spot and the Great Red Spot from the earliest recorded observations through the 21st century.

The team also performed numerous numerical computer simulations testing different models for the behavior of the vortex in Jupiter’s atmosphere that is the likely cause of the Great Red Spot. It is essentially a massive, persistent anticyclonic storm. In one of the models the authors tested, the droplet forms in the wake of a massive superstorm. Alternatively, several smaller eddies created by wind shear may have coalesced, or there may have been an instability in the planet’s wind currents that resulted in an elongated droplet-shaped atmospheric cell.

Sánchez-Lavega etc. concluded that the current Red Spot is probably not the same as the one observed by Cassini and others in the 17th century. They argue that the permanent spot had faded by the early 18th century and a new spot formed in the 19th century – the one we observe today, making it more than 190 years old.

Public domain/Eric Sussenbach

But maybe it is?

Others, like astronomer Scott Bolton of the Southwest Research Institute in Texas, remain unhappy with the conclusion. “What I think we can see is not that the storm went away and then a new one came in almost exactly the same place,” he told New Scientist. “It would be a very big coincidence if it happened at the same exact latitude, or even a similar latitude. It could be that what we’re really seeing is the evolution of the storm.”

Numerical simulations ruled out the merging vortices model for droplet formation; it is much more likely to be due to wind currents producing an elongated atmospheric shell. Furthermore, in 1879 the red dot measured about 24,200 miles (39,000 kilometers) on its longest axis and is now about 8,700 miles (14,000 kilometers). So the country has shrunk over the following decades and become more rounded. More recent observations by the Juno mission also revealed that the spot is thin and shallow.

The question of why the Great Red Spot is shrinking remains a matter of debate. The team plans further simulations aimed at reproducing the contraction dynamics and predicting whether the spot will stabilize at a certain size and remain stable or eventually disappear as Cassini’s permanent spot apparently did.

Geophysical Research Letters, 2024. DOI: 10.1029/2024GL108993 (About DOIs).